Chess

A game of perception

Chess forces us to engage in an “internal dialogue” with the self or the mind. It is a way of materializing our subconscious mind into the physical realm. Every time we play chess, we are able to “see” and “examine” our minds.

This opens us to review our perceptions of black and white, right wrong, illusion and reality.

Is there a difference of significance or is everything the same, or is everything an illusion, Maya? And if so? Why battles or conflicts.

My work is inspired by Yoko Ono “white chess”.

In Yoko Ono’s work PLAY IT BY TRUST aka WHITE CHESS from 1966. The instructions read “Play a game of chess as long as you can remember where all your pieces are“.

My work – using pieces covered in newspaper all of the same color is to rob the game of its purpose, a conflict of black and white.

It there after poses questions on perception and reality.

A matter of Taste

Taste is a design process of the sensory mind. “Taste” is simply the ability to draw on patterns and experience to identify an input and link it to a category of taste.

Taste is also a nomenclature used to define aesthetics. Good taste, bad taste or no taste at all.

A grouping under different taste symbolizes pattern recognition, so essential in competitive chess strategy.

The chess set has glass containers of the same shape, and size filled with sauces, vinegars and juices segregated into two groups red and black.

Ab initio they are all located in positions on a chess board according to hierarchy, but once the game commences, the chess pieces can only be identified by the taste of the ingredient inside the bottle.

The chess strategy based on pattern recognition in this chess set, will also need memorizing taste and linking it to each piece, both red and black.

This increased complexity of the game represents the increasing complexities of globalization, the change in ground realities and the evolving nature of new strategies to succeed.

The red and black also represents the new emerging economic power blocs, the west and the east in global realities and new emerging conflicts.

Chess and Conflict

The aim of sculptural chess pieces is to deconstruct conflict, to see conflict as a non-zero-sum situation, where both parties can win or both can lose. That is to expand the pie.

A conflict transformation option essential in a bipolar world of, rich and poor, north and south, east and west and conflicting priorities.

To reach this realisation of a non-zero sum option in decision making, I have chess boards, with different kinds of pieces using different sensory interface with the mind.

A traditional game of chess uses the sensory interface of sight, to see, locate and identify the pieces, to then decide strategy, and then uses the motor nerves to execute the moves.

I have introduced the sensory inputs of taste, sound, and smell along with sight as the sensory interface in different chess sets. This is to reflect the range of situations in conflicts.

In competitive chess, the Zero-sum game, the total benefit to all players in the game, for every combination of strategies, always adds to zero (more informally, a player benefits only at the equal expense of others).

In my five different conflict styles represented by different chess sets, I have represented people and groups inter-acting with other people or groups. Potential confrontations, where two actors are negotiating in order to obtain what they want. This confrontation could actually lead to different outcomes: some players could have won over the other party, some could reach a compromise, and some could be both satisfied. In some cases no one is satisfied with the outcome. There are three possible outcomes:

One wins, the other loses; Both win; Both lose;

Frequently, those in conflict thinks that one party will win and the other will lose. Here the parties perceive the conflict as a zero-sum situation, i.e. a situation where the gain of one part corresponds to the loss of the other. In other words, the outcome is seen as a fixed pie: the more I get of it the less you’ll get; if I get it all you’ll get none. In compromise we split the pie.

Nonetheless, experience tells us that very often in violent conflicts both parties lose. Frequently, if no party can impose self over the other(s) and they cannot compromise, the costs of fighting of each party will be so high that – no matter what the gain is – costs are higher. In other words, frequently parties in conflict lose more than they gain.

My work is an introspection of conflict and the futility of an adversarial world.

A Conflict of Fragrance

“Smell cannot be readily contained, they escape and cross boundaries, blending different entities into olfactory wholes. A sensory model opposed to our modern linear world view with its emphasis on divisions and interactions.”

I have used the blending of smell as a medium of artistic expression and creation by stimulating our nose to prove that in art and in life, there is a blending of sensory perceptions and no firm boundaries.

In 1965, the Japanese artist, Takako Saito, member of the Fluxus group, created a Smell chess by replacing chess pieces with bottles containing different scents of spices.

In my work a conflict of fragrance the players have to smell the pieces before deciding their moves. Their strategy in “the conflict of fragrances” has to involve the sensory perceptions of sight and smell in a sensory interface with the mind.

Smell is the one sense that has been repressed because of its power. According to Anthony Synott, “smell has been marginalized because it is felt to threaten the abstract and impersonal regime of modernity by virtue of its radical interiority, its boundary-transgressing propensities and its emotional potency.”(1) Odours go straight to the brain, bypassing any rational thought or processing–our reactions to them cannot be controlled, and therein lies the threat.

In Saito’s chess, strategy is undermined by the physical need to utilize the five senses…by involving senses that were normally unrelated to the traditional game, Saito transformed the ultimate conceptual game into a play of sensuous interactions.

The world of perfume is immense. Hundreds of new perfumes emerge on the market every year. Companies spend billions on packaging, marketing, advertising, and research. Despite the ubiquitous presence of fragrances in our daily lives, from our laundry detergent to the odours coming out of trendy Fifth Avenue stores guarded by hot young guys without shirts on the millions of smells that greet you each day.

Perfumes impact our world more than we realize. The immediate and involuntary reaction of hunger that happens when we walk by a bakery, the way we scrunch our noses at the smell of skunk, are signs of how hard-wired we are to our sense of smell. For millennia, priests throughout the world have burnt fragrant woods as offerings to higher gods and spirits. Nations waged wars over the ability to freely trade in teas, cinnamon, cloves, and cardamom. It is said that perfumes became popular when merchants transported silks from Asia with patchouli leaves around them to ward off pests. The European ladies who bought the fabrics loved the odour so much that a whole industry of perfumery was created to meet the demand.

There is a fascinating social and cultural history behind fragrances. They help to trigger emotions, memories, and images.

Diagnostic chess

Medical diagnosis and a game of chess have a lot in common, starting from analysis to prediction and fast response. Both rely on pattern recognition to come to the best alternatives and strategies within limited time slots.

Thereafter using resources at command to execute strategies.

Diagnostic chess set uses a few tools of a pathology lab and symbolizes the conflict of medicine and illness and strategies designed, to ensure a symbolic eradication of disease and “check mate” or killing the virus.

The colour red and black is also to demarcate ground realities of the poor and the affluent, the south and the north, in the global conversation on control of illness and drug prices.

Strategy is of Essence

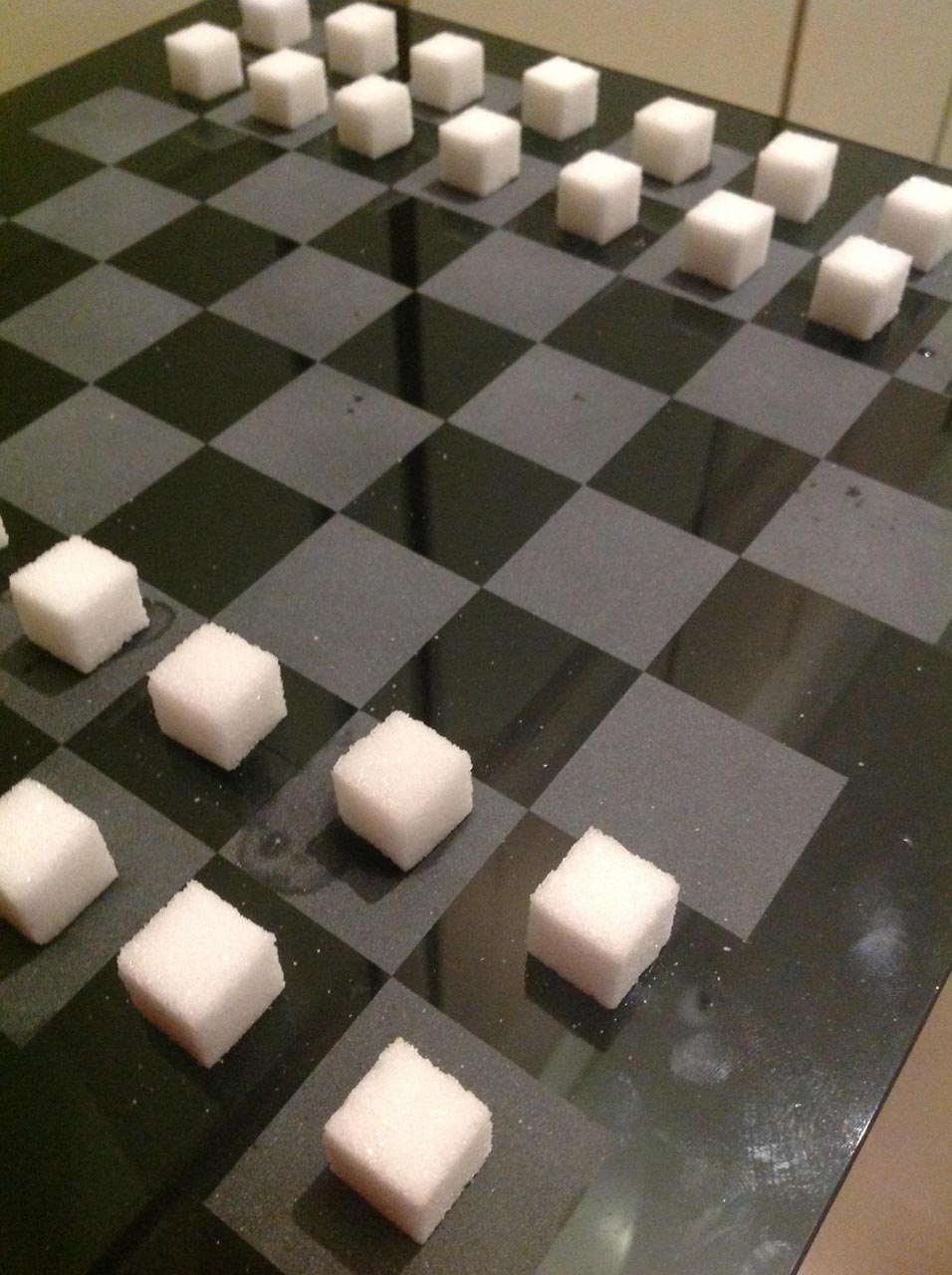

There are only white cubes of sugar on the chess board, all of the same size and colour.

The differences are, in the flavouring essences, on each sugar cube.

The flavouring essence adds distinctive smell and taste to each chess piece.

This game of chess, requires that, the players need to use their sensory perceptions of smell and taste aside from sight to play.

All pieces of the same colour denotes the universality of conflicts and the commonality of players as humans, in the conflict.

Only the essence differs.

Survival Games

The aim of sculptural chess pieces is to deconstruct conflict, to see conflict as a non-zero-sum situation, where both parties can win or both can lose. That is to expand the pie.

The aim of cultural chess pieces is to deconstruct conflict, to see conflict as a non-zero-sum situation, where both parties can win or both can lose. That is to expand the pie.

A conflict transformation option essential in a bipolar world of, rich and poor, north and south, east and west and conflicting priorities.

To reach this realisation of a non zero sum option in decision making, I have chess boards , with different kinds of pieces using different sensory interface with the mind.

A traditional game of chess uses the sensory interface of sight, to see, locate and identify the pieces, to then decide strategy, and then uses the motor nerves to execute the moves.

I have introduced the sensory inputs of taste. sound, and smell along with sight as the sensory interface in different chess sets . This is to reflect the range of situations in conflicts.

In competitive Chess, the Zero-sum game, the total benefit to all players in the game, for every combination of strategies, always adds to zero (more informally, a player benefits only at the equal expense of others).

In my five different conflict styles represented by different chess sets, I have represented people and groups inter-acting with other people or groups. Potential confrontations, where two actors are negotiating in order to obtain what they want. This confrontation could actually lead to different outcomes: some players could have won over the other party, some could reach a compromise, and some could be both satisfied. In some cases no one is satisfied with the outcome. There are three possible outcomes:

- One wins, the other loses;

- Both win;

- Both lose;

Frequently, those in conflict thinks that one party will win and the other will lose. Here the parties perceive the conflict as a zero-sum situation, i.e. a situation where the gain of one part corresponds to the loss of the other. In other words, the outcome is seen as a fixed pie: the more I get of it the less you’ll get; if I get it all you’ll get none. In compromise we split the pie.

Nonetheless, experience tells us that very often in violent conflicts both parties lose. Frequently, if no party can impose self over the other(s) and they cannot compromise, the costs of fighting of each party will be so high that – no matter what the gain is – costs are higher. In other words, frequently parties in conflict lose more than they gain.

My work is an introspection of conflict and the futility of an adversarial world.

White Chess

The aim of sculptural chess pieces is to deconstruct conflict, to see conflict as a non-zero-sum situation, where both parties can win or both can lose. That is to expand the pie.

The aim of cultural chess pieces is to deconstruct conflict, to see conflict as a non-zero-sum situation, where both parties can win or both can lose. That is to expand the pie.

A conflict transformation option essential in a bipolar world of, rich and poor, north and south, east and west and conflicting priorities.

To reach this realisation of a non zero sum option in decision making, I have chess boards , with different kinds of pieces using different sensory interface with the mind.

A traditional game of chess uses the sensory interface of sight, to see, locate and identify the pieces, to then decide strategy, and then uses the motor nerves to execute the moves.

I have introduced the sensory inputs of taste. sound, and smell along with sight as the sensory interface in different chess sets . This is to reflect the range of situations in conflicts.

In competitive Chess, the Zero-sum game, the total benefit to all players in the game, for every combination of strategies, always adds to zero (more informally, a player benefits only at the equal expense of others).

In my five different conflict styles represented by different chess sets, I have represented people and groups inter-acting with other people or groups. Potential confrontations, where two actors are negotiating in order to obtain what they want. This confrontation could actually lead to different outcomes: some players could have won over the other party, some could reach a compromise, and some could be both satisfied. In some cases no one is satisfied with the outcome. There are three possible outcomes:

- One wins, the other loses;

- Both win;

- Both lose;

Frequently, those in conflict thinks that one party will win and the other will lose. Here the parties perceive the conflict as a zero-sum situation, i.e. a situation where the gain of one part corresponds to the loss of the other. In other words, the outcome is seen as a fixed pie: the more I get of it the less you’ll get; if I get it all you’ll get none. In compromise we split the pie.

Nonetheless, experience tells us that very often in violent conflicts both parties lose. Frequently, if no party can impose self over the other(s) and they cannot compromise, the costs of fighting of each party will be so high that – no matter what the gain is – costs are higher. In other words, frequently parties in conflict lose more than they gain.

My work is an introspection of conflict and the futility of an adversarial world.